Introduction

Medical interpreters improve health outcomes for patients with limited English proficiency (LEP) due to decreased communication errors, improved patient comprehension, and improved overall patient satisfaction.1-3 Interpretation lowers readmission rates and lowers estimated hospital expenditures for patients with LEP.4 Though these benefits of medical interpreters are widely known, interpreters are underutilized in clinical settings.5-8

Only a fraction of medical schools in the United States have current curricula on working with medical interpreters and patients with LEP.9 Furthermore, many residents have also never received formalized training on interpreter use.10

The purpose of this study was to identify barriers to effective medical interpretation use for physician trainees. We hypothesized that physician trainees perceive barriers to using medical interpretation devices, and do not utilize or improperly utilize medical interpreters due to lack of access, lack of time, and lack of formal training. A secondary objective was to identify possible solutions to overcome barriers.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included a single US allopathic medical school with an affiliated hospital that utilizes a third-party medical interpreter service available in both inpatient and outpatient settings. The provider selects a language on an iPad and an interpreter is called through a video chat.

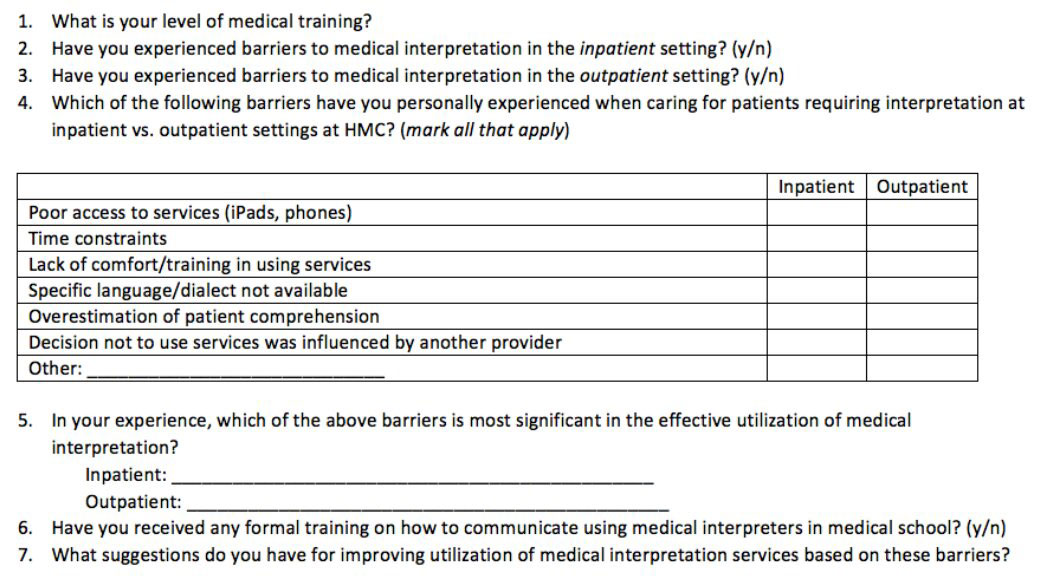

A seven-question anonymous survey was created and distributed to medical students and internal medicine residents (Figure 1). Surveys were distributed in person. Those administering the survey were given a script to follow to provide participants with a short description of the study’s background and goals prior to completing the survey. Students who had completed the internal medicine clerkship and internal medicine residents were chosen given the wide usage of medical interpretation in internal medicine inpatient wards and outpatient clinics. There was no compensation for completing the survey and there was no follow-up if a subject did not complete the survey.

The survey assessed presence of barriers, types of barriers, most significant barrier, potential solutions, and prior training. Specific barriers listed were poor access to services, time constraints to using medical interpreter, lack of comfort or training in using services, specific language not available on devices, overestimation of patient comprehension (the perception that the patient could understand well enough without the use of an interpreter), decision not to use services was influenced by another provider, or other barriers. These specific barriers were chosen from a preliminary focus group of eight fourth-year students who have completed their internal medicine clerkship and used medical interpreters.

The study was exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at Penn State Hershey Medical Center. Descriptive statistics were presented for participant characteristics and survey items. A chi-square test was conducted to determine if proportion of respondents who encountered barriers was different based on training level. All statistical analyses were conducted.

Figure 1. Medical Interpreter Survey Questions: survey questions sent to third- and fourth-year medical students, as well as internal medicine residents.

Results

Demographic Information

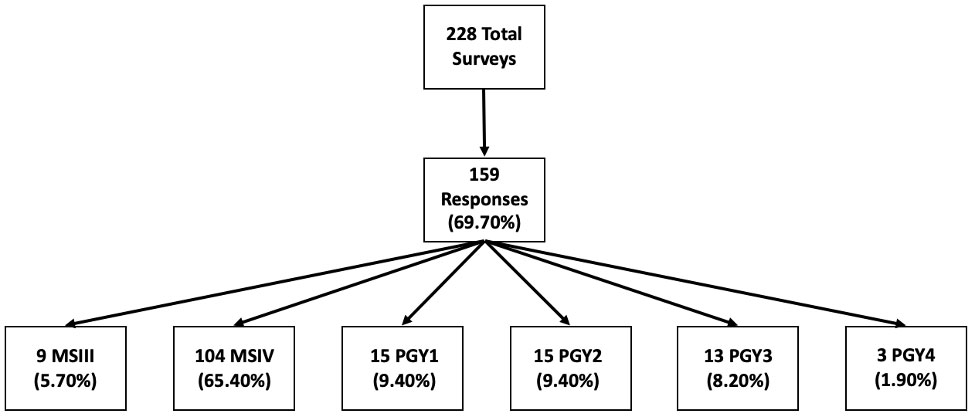

The survey was distributed to 228 third- and fourth-year medical students and internal medicine residents. The response rate was 69.74%, for a total of 159 completed surveys. Of those that completed the survey, 5.66% were third-year medical students, 65.41% were fourth-year medical students, 9.43% were first-year residents, 9.43% were second-year residents, 8.18% were third-year residents and 1.89% were fourth-year residents. There was no statistically significant difference between proportion of respondents who encountered barriers based on training level (p = 0.31).

Inpatient Barriers

Overall, 93.08% of respondents perceived barriers to medical interpretation in the inpatient setting. The most commonly reported barriers were time (76.26%), lack of access (71.94%), overestimation of patient comprehension (58.27%) and lack of comfort or training (43.88%). Trainees generally indicated that time (42.61%), access (41.74%) and overestimation of patient comprehension (8.70%) were their most significant barriers.

Outpatient Barriers

Likewise, 89.94% of respondents perceived barriers to medical interpretation in the outpatient setting. The most commonly reported barriers were time (84.85%), access (64.39%), overestimation of patient comprehension (53.03%), and comfort (38.63%). Respondents indicated that time (60.18%), access (23.89%) and comfort (7.08%) were the most significant barriers (Table 1).

Outpatient Barriers

Likewise, 89.94% of respondents perceived barriers to medical interpretation in the outpatient setting. The most commonly reported barriers were time (84.85%), access (64.39%), overestimation of patient comprehension (53.03%), and comfort (38.63%). Respondents indicated that time (60.18%), access (23.89%) and comfort (7.08%) were the most significant barriers (Table 1).

Figure 2. Demographic information: total surveys distributed, total response rate.

Formal Training and Improvements

Of those surveyed, only 21.40% had previous formal training in working with medical interpreters. Commonly listed suggestions for improvement were to increase access to the medical interpreter devices (38.17%) and provide formal training (31.30%) (Table 2).

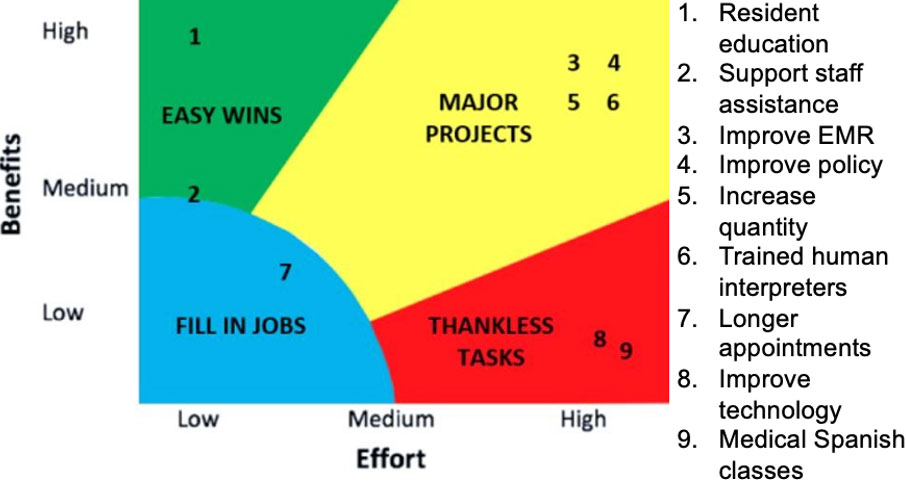

Based on participant responses, a benefit-effort matrix was constructed to determine the most feasible and impactful solutions. Using this model, we determined that resident education with formalized training in medical interpretation is an “easy win” (Figure 3).

Table 1. Perceived barriers to utilization of medical interpreter devices

Overestimation of Understanding: Overestimation of patient’s understanding; Comfort/Training: Comfort/training was insufficient; Language unavailable; Language was not available on device; Family Member: Family member used as interpreter. Trainees reported all barriers faced, both inpatient and outpatient, then identified what they felt was the most significant factor.

|

Time |

Access |

Overestimation of Understanding |

Comfort/Training |

Language unavailable |

Technology Issue |

Family Member |

|

|

Inpatient |

106 (76.26%) |

100 (71.94%) |

81 (58.27%) |

61 (43.88%) |

26 (18.71%) |

13 (9.35%) |

4 (2.88%) |

|

Most Significant Barrier n (%) |

49 (42.61%) |

48 (41.74%) |

10 (8.7%) |

9 (7.83%) |

2 (1.74%) |

3 (2.61%) |

0 (0%) |

|

Outpatient |

112 (84.85%) |

85 (64.39%) |

70 (53.03%) |

51 (38.63%) |

27 (20.45%) |

8 (6.06%) |

4 (3.03%) |

|

Most Significant Barrier n (%) |

68 (60.18%) |

27 (23.89%) |

7 (6.19%) |

8 (7.08%) |

4 (3.54%) |

2 (1.77%) |

3 (2.65%) |

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the vast majority of respondents reported barriers to utilization of medical interpreters in the inpatient and outpatient setting. The most common and significant barriers identified were access to the medical interpreter device and lack of time. Importantly, only a fraction of the students and residents surveyed had previous formalized training in working with medical interpreters. The results are consistent with our hypothesis.

Previous studies also demonstrate the need for better access to medical interpreters and more time per visit for patients with LEP. A recent study was conducted to evaluate whether increasing the number of medical interpreters in an urgent care center will increase the usage frequency and satisfaction of the application. The study showed that by increasing access to medical interpreters, usage had increased threefold and clinicians were satisfied with the use of the application and access to the language services.10 Another study assessed the total time that medical interpreters add to a patient’s office visit. Using a videoconference method to provide the patient with a medical interpreter adds an average of 4.70 minutes to a patient’s visit.11

Using a benefit-effort matrix, we determined that setting up formalized resident training would be an “easy win” because it would require little effort and provide a large benefit. A previous study recommending training for residents suggested a focus on topics such as the health impact of language barriers, optimal positioning of the interpreter, and maintaining eye contact with the patient during the encounter.12 Such training has been associated with improved knowledge and attitudes, higher self-assessed skill levels in working with interpreters, improved patient satisfaction, increased use of interpreters by providers and increased provider satisfaction with care.13-16

Limitations

Study limitations included distributing surveys only to students and residents from one academic institution, which may limit generalizability to other institutions with different medical training. In addition, this medical center serves a fairly homogenous population compared to urban regions of the country, which further which further limits generalizability. The use of internal medicine residents, rather than a residency-wide survey, may also limit generalizability to other specialties. Although those distributing the surveys were given instructions and a script on how to explain the survey to students and residents, there is risk of the Hawthorne effect, where participants respond differently when being observed.

Figure 3. Benefit-Effort matrix: potential solutions to barriers of medical interpretation of languages, proposed by survey respondents.

Conclusion

This study found that most trainees have experienced barriers to effective communication with patients with LEP. The most common and significant barriers to providing adequate care to this population is access to medical interpretation services and time. Even when providers have access and time, there are only a fraction that have formalized training in use of medical interpretation services. A feasible solution would be to provide education at the level of both medical students and residents in order to improve efficiency and ability with these important services during medical training. Future endeavors should focus on designing and implementing formalized resident education to focus on topics such as the health impact of language barriers, optimal positioning of the interpreter, maintaining eye contact with the patient during the encounter, and other strategies important for caring for LEP patients. Doing so has the potential to reduce medical errors, improve quality and delivery of care, and improve overall patient satisfaction for this vulnerable population.

Author Information

Corresponding Author

* Deep Patel, BS

dpatel3@pennstatehealth.psu.edu, 908-642-5095

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclosures

No authors have any disclosures or conflicts of interest at this time.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Carissa Harnish, Rachel Hannum, Amy Lu, Lori-Ann Glasgow, Yan Leyfman, Hayley Price and Timothy Winslow for their help in carrying out this project.

Table 2. Perceived barriers to utilization of medical interpreter devices.

Trainees reported all barriers faced, both inpatient and outpatient, then identified what they felt was the most significant factor.

|

Better Access |

Formalized Training |

Longer Appointment |

In-Person Translator |

Improve Technology |

Support Staff |

Systems (EMR Improvement) |

Provider Learn Language |

|

|

n |

50 |

41 |

10 |

10 |

7 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

|

% |

38.17% |

31.30% |

7.63% |

7.63% |

5.34% |

3.82% |

3.82% |

2.29% |

References

1. Karliner, L. S., Jacobs, E. A., Chen, A. H., & Mutha, S. (2007). Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health services research, 42(2), 727-754.

2. Silva, M. D., Genoff, M., Zaballa, A., Jewell, S., Stabler, S., Gany, F. M., & Diamond, L. C. (2016). Interpreting at the end of life: a systematic review of the impact of interpreters on the delivery of palliative care services to cancer patients with limited English proficiency. Journal of pain and symptom management, 51(3), 569-580.

3. Lee, J. S., Pérez-Stable, E. J., Gregorich, S. E., Crawford, M. H., Green, A., Livaudais-Toman, J., & Karliner, L. S. (2017). Increased access to professional interpreters in the hospital improves informed consent for patients with limited English proficiency. Journal of general internal medicine, 32(8), 863-870.

4. Karliner, L. S., Pérez-Stable, E. J., & Gregorich, S. E. (2017). Convenient access to professional interpreters in the hospital decreases readmission rates and estimated hospital expenditures for patients with limited English proficiency. Medical care, 55(3), 199.

5. Patel, D. N., Wakeam, E., Genoff, M., Mujawar, I., Ashley, S. W., & Diamond, L. C. (2016). Preoperative consent for patients with limited English proficiency. Journal of surgical research, 200(2), 514-522.

6. Lee, J. S., Nápoles, A., Mutha, S., Pérez-Stable, E. J., Gregorich, S. E., Livaudais-Toman, J., & Karliner, L. S. (2018). Hospital discharge preparedness for patients with limited English proficiency: a mixed methods study of bedside interpreter-phones. Patient education and counseling, 101(1), 25-32.

7. Gray, B., Stanley, J., Stubbe, M., & Hilder, J. (2011). Communication difficulties with limited English proficiency patients: clinician perceptions of clinical risk and patterns of use of interpreters. NZ Med J, 124(1342), 23-38.

8. Schenker, Y., Pérez-Stable, E. J., Nickleach, D., & Karliner, L. S. (2011). Patterns of interpreter use for hospitalized patients with limited English proficiency. Journal of general internal medicine, 26(7), 712-717.

9. Himmelstein, J., Wright, W. S., & Wiederman, M. W. (2018). US medical school curricula on working with medical interpreters and/or patients with limited English proficiency. Advances in medical education and practice, 9, 729.

10. Narang, B., Park, S. Y., Norrmén-Smith, I. O., Lange, M., Ocampo, A. J., Gany, F. M., & Diamond, L. C. (2019). The Use of a Mobile Application to Increase Access to Interpreters for Cancer Patients With Limited English Proficiency: A Pilot Study. Medical care, 57, S184-S189.

11. Locatis, C., Williamson, D., Gould-Kabler, C., Zone-Smith, L., Detzler, I., Roberson, J., ... & Ackerman, M. (2010). Comparing in-person, video, and telephonic medical interpretation. Journal of general internal medicine, 25(4), 345-350.

12. Thompson, D. A., Hernandez, R. G., Cowden, J. D., Sisson, S. D., & Moon, M. (2013). Caring for patients with limited English proficiency: are residents prepared to use medical interpreters? Academic Medicine, 88(10), 1485-1492.

13. Weissman, J. S., Betancourt, J., Campbell, E. G., Park, E. R., Kim, M., Clarridge, B., ... & Maina, A. W. (2005). Resident physicians’ preparedness to provide cross-cultural care. JAMA, 294(9), 1058-1067.

14. Wu, A. C., Leventhal, J. M., Ortiz, J., Gonzalez, E. E., & Forsyth, B. (2006). The interpreter as cultural educator of residents: Improving communication for Latino parents. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 160(11), 1145-1150.

15. Jacobs, E. A., Diamond, L. C., & Stevak, L. (2010). The importance of teaching clinicians when and how to work with interpreters. Patient education and counseling. 78(2), 149-153.

16. Karliner, L. S., Pérez-Stable, E. J., & Gildengorin, G. (2004). The language divide. Journal of general internal medicine, 19(2), 175-183.