What distinguishes a profession from a vocation? What job responsibilities specific to academic advising make it unique from related career areas? Can advising be learned solely on the job? Why or why not?

These are the guiding questions that prompted investigation into the occupation of academic advising and ultimately a presentation at the Utah Advising and Orientation Association (UAOA) annual conference in 2011. There were additional reasons for exploring this topic as well. First, published literature regarding established professions and academic advising as it relates to a profession is limited. Second, academic advisers seem to question whether they work in a profession or simply work in accordance with professional standards or practices. Third, there has been a steady increase of publications, conversations, and presentations surrounding the topic of academic advising as a profession. None of these reasons fully explores or offers a consensus on whether or not academic advising is a profession or if academic advisers should work toward professionalizing the field in the future. Examining academic advising as a field of inquiry, Habley explained, “Advising still has some distance to travel before one can claim it on equal footing with other areas of higher education inquiry. It is yet to be recognized as a branch of learning, a field of study, a discipline, or a profession,” (2009, p. 80). “Based on published discipline-oriented research findings in adjudicated journals and acceptance as a degree-granting area,” Kuhn and Padak concluded “that academic advising must establish more credentials before it can be considered an academic discipline” (2008, p. 3).

Criteria for recognized professions

According to several sociological and historical sources, there are specified criteria an occupation must meet in order to become a recognized profession. Wilensky (1964, p. 141) asserted there are actually very few occupations, perhaps thirty to forty that are fully professionalized. He further explained this number is variable and dependent on the amount of overlap between disciplines. For an occupation to reach professional status, four criteria must be met. Wilensky (1964) stated, “Any occupation wishing to exercise professional authority must find a technical basis for it, assert an exclusive jurisdiction, link both skill and jurisdiction to standards of training, and convince the public that its services are uniquely trustworthy” (p. 138). Alan Klass (1961) echoed the sentiment when he wrote that a profession must include scholarship, research, self governance, sole jurisdiction, and public service (pp. 699–700). These criteria and opinions are echoed in recent publications (Kuhn & Padak, 2008; Habley, 2009; Shaffer, Zalewski, & Leveille, 2010; Evetts, 2003; Kolb, 2008; and Macionis, 2007).

Presentation explanation

Our goals for the UAOA presentation were to provide a forum in which advisers would respond to questions about their current job duties, contribute demographic information, learn about professionalization, share their understanding of professionalization, and discuss the future of academic advising. Specifically, we utilized TurningPoint™ technology (clickers) to collect responses from participants. We chose this type of survey methodology so attendees could view results instantaneously versus complete a paper survey and learn of the results later. Instant feedback would help to facilitate lively and open discussion. Moreover, responses were anonymous to encourage participants to express their true opinions without fear of repercussion from peers or supervisors. However, while clickers gave respondents the ability to respond in real time, TurningPoint™ technology also permitted respondents to opt out of answering. For this reason, the respondent pool fluctuated from a low of 53 to a high of 58. Consequently, data results are primarily given as percentages.

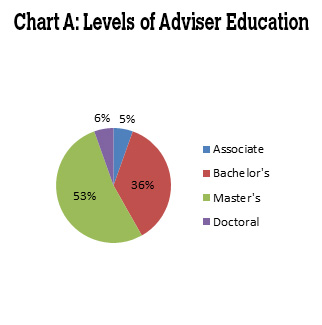

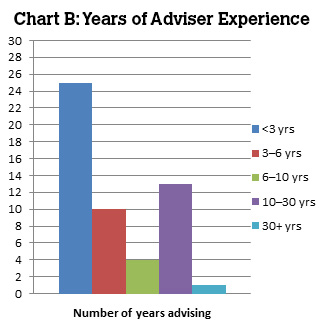

Attendees who participated in the presentation represented the following higher education institutions in the state of Utah: The University of Utah, Utah State University, Weber State University, Southern Utah University, Snow College, Dixie State College, Utah Valley University, Brigham Young University, and Salt Lake Community College. The results cannot be generalized outside of this population. The majority of respondents were new advisers with 47 percent having advised fewer than three years; 30 percent had advised more than six years. Lastly, only one person reported advising more than thirty years. An overwhelming majority of advisers—88 percent—indicated they were employed as full-time advisers working thirty or more hours per week in their positions. With respect to the level of education represented by the group, all participants had earned at least a bachelor’s degree with the exception of three respondents who had earned associate degrees (Chart A). Twenty-nine of the fifty-five respondents had earned master’s degrees, and three persons in the group had each earned a doctoral degree. As such, this group represented a high level of education with relatively few years of professional academic advising experience (Chart B).

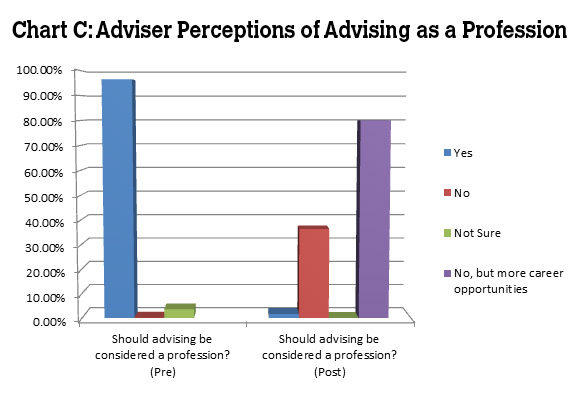

During the presentation, we asked a total of twelve questions. The first three questions were demographic and allowed the users to become familiar with the technology. The fourth question established a baseline understanding of participants’ thoughts regarding advising as a profession. We anticipated advisers knew little of the technical criteria describing a profession, and our overarching goal was to determine whether participants’ opinions changed after learning more about professionalization. We asked this baseline question concerning professionalization a second time as a post-test to conclude the presentation.

Findings

Ninety-six percent of respondents answered “yes” when asked the baseline question, “Do you think advising should be considered a profession?” This reporting is interesting, because when the same question was asked at the end of the presentation, respondents drastically shifted their answers. For the post-test question, only 16 percent answered “yes;” 3 percent answered “no,” and 80 percent of respondents answered, “no, but additional career opportunities should be provided.” These data suggest that once respondents learn more about professionalization or the implications of professionalization for advising, most think it is not the most appropriate choice (Chart C). Results from the other questions provide information on what the audience learned and why they changed their responses at the end of the presentation.

Established professions require a long tertiary education usually resulting in an advanced degree. When asked what the minimum level of education for a professional adviser should be, the majority responded that a bachelor’s degree should be the minimum qualification (61 percent). This suggested, according to advising practitioners in this group, academic advising does not warrant the long tertiary education required of a profession.

Interestingly, the majority of the group had earned more than a bachelor’s degree (Chart A) but did not report that level of education was necessary to fulfill the responsibilities of advising. This response could reflect the underutilized skills and talents of advisers and advising office employee resources. Perhaps these advisers did not believe they use the skills they gained through their educations. Many of these offices and their employees may be advising at a lower standard than would be required of advising if it were professionalized.

Next, we addressed the second tenet of a profession: sole jurisdiction. Our research found that all recognized professions have exclusive authority over the tasks they perform. This means only those who are licensed, certified, or approved can practice the skills and accept responsibility for the professional service. For advising, only those who are approved to advise would be allowed to solicit, advertise, or use the title of an adviser. Sole jurisdiction necessitates a similarity of duties or responsibilities for all those who practice. For advising to enjoy self-jurisdiction, the field of advising must create a clear definition of the occupation, to include the responsibilities, procedures, scope of practice, and professional practices all advisers would follow. Advisers would not be expected to work outside those job duties nor would any other occupation be allowed to perform the delineated duties of the adviser. After briefly describing sole jurisdiction to the attendees, we presented two lists of academic advising duties. The first was a compilation of typical advising tasks that most if not all advisers reportedly perform:

- Provide general education guidance

- Develop advising handbooks

- Participate on academic policy committees

- Evaluate transfer credits

- Monitor degree audits

- Serve as liaisons to academic departments or schools

The second list included job duties typically reported from higher-level administrators and that some advisers or advising offices have reported performing:

- Research

- Curriculum

- Assessment and development

- Service (academic committees, national committees)

- Publications

- Accreditation

- Student services

Nearly 70 percent of the attendees “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that advisers should be involved with the job duties from the second list. These “higher-level” activities are more similar to responsibilities required in other professions and are acquired through a tertiary education, years of practical experience, and a strong theoretical background.

The responses to these questions seemed to contradict the earlier finding that the minimum degree required for advising is a bachelor’s degree. If the occupation of advising should include these “higher-level” activities, one might wonder how well an employee, holding solely a bachelor’s degree, could perform these activities. It may be that the audience wrongly assumed someone without prior educational training could learn these activities on the job. While it is true that some of these tasks can be repeated or mimicked, it would be a mistake to assume that most employees with bachelor’s degrees could successfully conduct research or assessment or add insightful comment to curriculum committee work without a greater knowledge of higher education and how these tasks are performed.

Third, we assessed the participants’ understanding of self-regulation. Technically, academic advisers do not have a governing body or association that dictates the specific standards or job role to advisers. However, a professional association for advisers does exist as the National Academic Advising Association (NACADA). This group makes recommendations for best practices, encourages scholarly activities, and advocates for academic advising but has a limited impact on the daily job of an adviser. We asked attendees whether or not they had heard of NACADA or the Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (CAS) Standards. Fifty-six percent reported an awareness of one of these entities, while 44 percent reported no knowledge or “not sure.” Given the low level of awareness concerning these standards and guidelines, it is questionable whether advisers in this group would be able to effectively provide recommendations and contribute to discussions about the standards for higher education and the occupation of advising.

This finding was interesting to our study, because with such a large percentage of our group (53 percent) having earned master’s degrees and 53 percent with three or more years of advising experience, 44 percent of the participants had not heard of these academic advising standards. Upon closer examination of the data, 54 percent of the “no” and “not sure” respondents had master’s degrees or higher. What this might indicate is that advisers in our group who had earned master’s degrees had completed programs outside the area of higher education; thus, they might not have had the opportunity to learn about the recommended standards currently in place for advising programs. Regardless, lack of professional standards and policies for advising does not reflect well on an occupation that has historically hoped for professionalization. Conversely, without a professional organization providing advisers with policies, procedures, scope of practice, and other professional standards, a lack of knowledge regarding standards seems not entirely the fault of academic advisers.

Lastly, we polled the group to discover whether participants thought advisers provide a necessary public service to a vulnerable population that relies heavily on the advising expert. An overwhelming majority, 96 percent, reported they agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. Inherent in the nature of advising is providing a service to assist students in obtaining their educational goals. Kuhn and Padak (2008) describe the way in which advisers provide a service to students, “To the degree that it contributes to the assistance, help, use, benefit, and welfare of students, academic advising is a service.” In addition, there is some consensus that students are (or should be considered) increasingly vulnerable because of the significant financial investment to obtain an education, disconnect that sometimes exists between a college major and a concrete career path, the uncertain job market, the inherent vulnerability of students in this stage of development, and the low percentage of people who attempt and successfully obtain a bachelor’s degree.

The responses to this question indicated a significant level of agreement with the fourth tenet found in recognized professions: provide a necessary public service. A second part of this tenet is the sacrifice required of professionals in various areas of their lives to best serve their populations. Typically, a professional might have to sacrifice regular 9-to-5 schedules and personal commitments to serve their populations. Attendees were fairly divided when asked whether they would sacrifice these items: 37 percent reported yes, 32 percent reported no, and 30 percent reported maybe. This piece of information is interesting, because the split in responses could indicate that advisers are uncertain about the expectations in their career field, yet these responses may indicate most respondents are willing to trade some of the 9-to-5 norms for the benefits of professionalization. The respondents who were not willing to forgo 9-to-5 norms may indicate an unwillingness to change these norms; however, because a great deal of discussion revolved around this question, it is more likely that these negative responses indicate a lack of adequate information.

Overall, the data from this presentation highlight the confusion many advisers might have about their career field. This confusion is evidenced by respondents’ answers to professionalization criteria questions that were inconsistent with the pre-presentation rate of 96 percent who believed advising should be considered a profession. While not present in the data, the enthusiasm, attention, and concern for this topic were ever present. This indicates a high interest in this topic and perhaps a lack of information about it. It seems clear that there is disagreement, if not confusion, about what types of job duties an adviser should be expected to participate in and how professionalization may impact the occupation of academic advising.

Future directions and impact on advising

Through our research we discovered that many academic advisers are concerned about career progression. Many have expressed interest in exploring options that would offer promotional opportunities within advising. When participants were asked at the end of the presentation whether academic advising should be a profession, 80 percent responded “no” but that career opportunities should be provided. This answer was a significant shift from participants’ responses at the beginning of the presentation when 96 percent of respondents indicated they believed advising should be considered a profession. At some institutions, internal processes for promotion already exist. At other institutions, advisers are forced to forge their own career paths with no existing structure. Other advisers rely on mentors or more experienced advisers for assistance when determining the route they should pursue within higher education. It is not uncommon for many advisers to feel forced to assume additional responsibilities unrelated to advising in order to be promoted or receive raises or recognition within the institution.

We found commonalities within the literature with respect to the type of information that should be gathered in order for academic advising to become a recognized discipline and profession. Kuhn and Padak (2008) asserted that a unique and credible knowledge body needs to be strengthened, clear modes of inquiry that demonstrate how academic advising is validated need to exist, and new knowledge needs to be created by advisers. Once these criteria have been met in a more concrete manner, academic advising can advance as an academic discipline. Habley (2009) also agreed there are further steps to take for academic advising to become an established field of inquiry and explained, “to date, a unique and credible body of knowledge is nonexistent, evidence supporting the impact of advising is insufficient, and a coherent and widely delivered curriculum for advising is currently unavailable” (p.82). Finally, McGillin (2000) stated a top priority for academic advising is to develop a theory of advising: “We must first clarify what advising is and is not by generating a theory of academic advising” (p.374).Pending these additions, academic advising could be considered a more defined field of inquiry and a more complete academic discipline with an avenue for professionalization available, if chosen.

Our advising group plans to continue to conduct research by traveling across the country to gather feedback from advisers. With a few revisions, we will continue with the presentation format discussed above. The research results from these studies should provide data on how advisers define a profession, how advisers define their careers, whether professionalization is an appropriate match for advising, and if so, how might advisers qualify for and achieve professional levels within their field. The findings will have implications for policy, practice, occupational status, occupational definition, and future research involving the topic of academic advising as an occupation.