Meta-assessment, or the post-assessment cycle process of evaluating the effectiveness and quality of an assessment program, is a relatively new methodological approach in higher education. A small but growing literature has proposed and discussed the utility of implementing meta-assessment (Bresciani et al., 2009; McDonald, 2010; Ory, 1992; Palomba & Banta, 1999; Rodgers et al., 2013; Schoepp & Benson, 2016). However, meta-assessment of academic disciplinary programs has been scant (cf. Fulcher, 2018; St. Cloud State University, 2015), and meta-assessment is not yet formally occurring outside of academic disciplinary programs. The relative lack of scholarly literature and limited implementation of meta-assessment in practice are unfortunate, given the increase in assessment activities in higher education and the use of assessment results as the basis for significant decisions.

According to existing literature, meta-assessment involves identifying key questions and expectations regarding the initial assessment processes and evaluating whether those processes were correctly performed. More specifically, meta-assessment as described in existing literature involves the examination of (a) the initial need for assessment, (b) the elements included in the assessment process, (c) the necessary and sufficient conditions required for a valid assessment process, and (d) whether the appropriate actions were taken based on the assessment results (Ory, 1992; McDonald, 2010; Schoepp & Benson, 2016).

Following this conceptualization, meta-assessment can help ensure the validity of the assessment process and, in turn, the validity of assessment results as the basis for decisions. Ideally, initial assessment processes are executed correctly, and critical stakeholders are educated on the appropriate methodologies and the validity and reliability of empirical research procedures. In such a best-case scenario, one could appropriately rely on outcome data to make educational program and policy decisions. However, in reality, assessment processes are never executed perfectly and ultimately invalid outcome data may be used to make decisions. Meta-assessment serves as a post hoc safety net regarding the usefulness of the outcome data. While this is vital for programmatic needs, it is also important if planning to present local assessment results as scholarly inquiry, such as at a professional conference or through publication.

EVALUATION VERSUS ASSESSMENT

Although meta-assessment as described above is useful, the term “assessment” in existing conceptualizations of meta-assessment is actually a misnomer. Unfortunately, the terms “evaluation” and “assessment” have historically been used interchangeably in the higher education literature (Baehr, 2005; Creamer & Scott, 2000; Cuseo, n.d., 2008; Lynch, 2000; Troxel, 2008). Evaluation typically involves indirect measurement of the perceived performance of the individual service provider, completed via episodic student satisfaction or student perception ratings (Habley, 2004; Macaruso, 2007; Robbins, 2011, 2016b). Evaluation may occur at the program level as well. Program evaluation, or program review, involves a holistic and comprehensive examination of a program via a self-study and/or an external review by experts in the appropriate field (Wholey et al., 1994). Program evaluation is conducted in order to meet internal and external accountability expectations, to benchmark goals, and to determine whether realistic outcomes have been achieved.

Assessment is the continuous, systematic process of collecting outcome data via multiple collection points and measures to determine what students know, understand, and can do with their knowledge resulting from their educational experiences (Huba & Freed, 2000). Assessment results are utilized to improve subsequent student learning and development (Angelo, 1995; Huba & Freed, 2000; Marchese, 1993; Palomba & Banta, 1999; Pellegrino et al., 2001).

Evaluation of individual provider performance may be included in an overall assessment designed to measure outcomes. However, evaluation alone proves insufficient to support claims of program effectiveness (or ineffectiveness) and student learning (Robbins, 2011; Robbins & Zarges, 2011). In addition, assessment results are included in a program evaluation and provide much of the data needed to demonstrate program effectiveness and worth, to support resource allocation and requests, and to identify needs for revision and professional development.

The conceptualization of meta-assessment in existing literature involves the review and evaluation of process but does not include any true assessment of learning. Reviewing and evaluating the assessment process—as existing literature on meta-assessment proposes—is certainly a valuable practice. However, we must also carry out “true” meta-assessment, that is determining the nature and extent of stakeholder learning from participation in the assessment process. Stakeholders could include the assessment team (i.e., the people collecting and analyzing the assessment data), students, service providers, faculty, administrators, etc.

Knowing what stakeholders have learned as a result of their experiences with the assessment process directly influences the validity of subsequent assessment cycles. For example, the assessment team’s involvement in the assessment process may be their only direct learning opportunity regarding assessment as a stakeholder cohort. The assessment team might participate in some brief introduction to assessment or a professional development opportunity regarding assessment; they might even have the opportunity to take a formal course on assessment in higher education. However, personally experiencing assessment promotes learning about students specific to the assessment team’s own campuses and programs, along with the campuses’ and programs’ specific missions, goals, and student learning outcomes (SLOs). The assessment team’s stakeholder learning outcomes may include a better understanding of the need for assessment of student learning, the ability to evaluate the validity of outcome data, and an understanding of subsequent actions based on the results of assessment. Note that these learning outcomes align with the elements of meta-assessment, Items a through d, listed at the beginning of this article. However, here they are reframed as issues of learning, knowledge, and understanding, rather than action or behavior. Ultimately, assessment of such stakeholder learning would help determine the necessity for additional assessment training or retraining.

For students as stakeholders, the learning outcomes resulting from participation in program assessment would be different from the desired SLOs resulting from the students’ interactions and experiences with the program. Example SLOs for participating in the assessment process may include understanding the necessity for assessment, knowing the difference between evaluation and assessment, and understanding the connection between assessment results and programmatic decision-making to promote student success. Regarding the service providers as stakeholders, desired learning outcomes may similarly include understanding the necessity for assessment, understanding the connection between assessment results and programmatic decision-making to promote student success, and knowing their roles in the assessment process, among others.

An understanding of the importance of assessment and the importance of the validity of the outcome data may be similarly desirable for external stakeholders, such as faculty and administrators, to learn from experience. Because assessment takes time and resources to conduct, external stakeholders may question why assessment of a specific program is necessary in the first place. In order for changes based on assessment results to be approved and supported, the assessment process must be understood by those with the authority to provide approval and resources for such changes. In short, there are various cohorts of stakeholders in the assessment process who should learn from the process for varying reasons.

Given the existing definitions of meta-assessment and the importance of stakeholder learning, I propose two specific questions when examining the usefulness and validity of an assessment process:

- Was the assessment process completed in an appropriate and methodologically sound manner?

- What did those involved in the assessment of the program learn as a result of their experiences?

I will refer to existing conceptualizations of meta-assessment, which correspond to Question 1, as evaluation of the assessment process and to “true” meta-assessment, which corresponds to Question 2, as assessment of the assessment process.

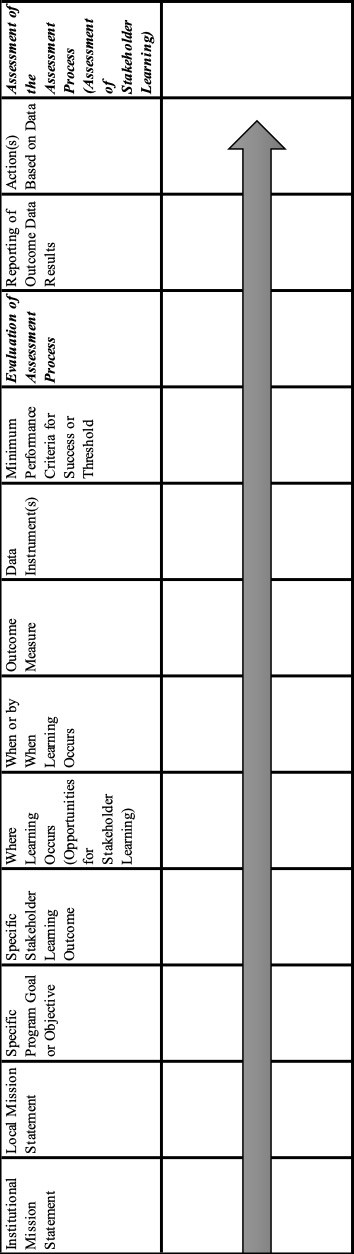

Table 1 provides an assessment matrix, adapted from Robbins (2009, 2011, 2016b) and Robbins and Zarges (2011), including these two components or conceptualizations of meta-assessment as additional steps in the assessment process. Evaluation of the assessment process should occur before the reporting of any results and “closing the loop” or making any changes based on the outcome data. This aspect of meta-assessment is employed to determine whether the assessment process was appropriate and valid, whether the methodology used was correct for the gathering and analysis of outcome data, and whether the final assessment data were, therefore, legitimate. To report data or, worse, to implement changes based on data that may be invalid, would be a mistake. Every check must be made to ensure the validity of the outcome data before reporting and acting upon it, which is the point of this post-assessment evaluation process.

Table 1

Assessment Matrix including two meta-assessment components.

Assessment of the assessment process, or assessment of stakeholder learning resulting from the assessment process, must occur after the completion of the assessment process (including the aforementioned evaluation of the assessment process) and before subsequent assessments of any new SLOs or implemented changes occur. One reason for this is to determine whether any additional training on the assessment process is needed for internal stakeholders such as the assessment team. This can also inform whether internal and external stakeholders understand the necessity for assessment of the program and the importance of conducting assessment correctly in order to make real improvements to promote student success. As such, a learning outcome for all stakeholders is that they understand the importance of the additional step of evaluating the initial assessment process before reporting or acting upon assessment results.

DEVELOPMENT OF SAMPLE RUBRICS

In order to help the reader understand what meta-assessment might look like in practice and to offer some suggestions for particular items to be evaluated or assessed, I have developed two preliminary sample rubrics. A rubric is a scoring scale utilized to measure performance against a predetermined set of criteria (Robbins, 2017; Stevens & Levi, 2005). It divides a desired outcome into its component parts, which serve as criterion points. The rubric provides explanations of appropriate degrees of performance for each criterion. Most rubrics have at least two criterion points and two levels of performance on separate axes. Construction of a rubric requires reflection on the overall objectives, goals, and outcomes of the program as well as identification of what specifically is to be accomplished by the program. Suskie (2009) suggested that rubrics are becoming the standard in higher education assessment. She proposed that they are particularly good choices when: important assessments are undertaken, which will contribute to major decisions; several people are involved in assessing the same learning outcomes; providing clear, detailed feedback on strengths and weaknesses is important; or skeptical audiences will be examining the rubric scores.

In developing the sample rubrics below, I have kept considerations around planning initial assessments in mind (cf. Robbins, 2009, 2011, 2016b; Robbins & Zarges, 2011) and have grounded sample rubrics in these general theoretical and applied bases:

- The program being assessed is part of the teaching and learning mission of the institution.

- Specific SLOs are achieved from the students’ experiences with the program.

- Assessment of SLOs is central to determining the program’s effectiveness.

- Programmatic changes and resource decisions are based on assessment data.

- The assessment of programmatic processes must be appropriate and valid.

I have utilized a four-point scale for both sample rubrics, as this is a simple and common scale used in rubrics. However, in practice scales should vary based on individual program needs. Any weighting of rubric items would also need to be determined locally, based on the program’s specific mission, goals, and needs. The rubrics offered here are simply samples to illustrate what meta-assessment might look like. If implemented, they may be revised and built upon to fit a particular program and context.

Table 2 proposes a sample model rubric for the review and evaluation of the assessment process, which corresponds to meta-assessment as described in existing literature. As mentioned previously, this existing conceptualization of meta-assessment involves evaluating (a) the initial need for assessment, (b) the elements included in the assessment process, (c) the necessary and sufficient conditions required for a valid assessment process, and (d) whether the appropriate actions were taken based on the assessment results (Ory, 1992; McDonald, 2010; Schoepp & Benson, 2016). This rubric includes components a, b, and c of the current meta-assessment paradigm, since appropriately acting upon the assessment results occurs only after it has been determined that the assessment results are indeed valid.

Not all of the attributes in the Table 2 rubric must be included to determine the appropriateness and effectiveness of an assessment process, and there may be additional attributes that need to be included for a given specific program. However, many of the identified attributes in the rubric are necessary and will be common for any evaluation of an assessment process. Such attributes involve the inclusion of all appropriate stakeholders, the listing of desired SLOs, the listing of necessary process/delivery outcomes (PDOs) to allow for the achievement of the SLOs, the appropriateness of outcome measures, and the level of sustainability of the assessment process, among others. The increasing use of technology to support and enhance higher educational programming is an additional growing consideration.

Table 2

| Attribute | Not Present/Absent Attribute is absent |

Minimally Present/Emerging Attribute has been attempted but deficiencies are evident |

Present but Not Completely Attribute is present but is not fully developed |

Highly Present/Complete Attribute is fully developed and consistently applied |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholders | ||||

| Appropriate stakeholders were included in the assessment planning | No relevant stakeholders were included in the planning process for assessment | Some relevant stakeholders were included in the planning process for assessment | Many, but not all, relevant stakeholders were included in the planning process for assessment | All relevant stakeholders were included in the planning process for assessment |

| Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs) | ||||

| A comprehensive list of desired individual SLOs reflecting the intended learning outcomes for the program exists | No identified SLOs exist that reflect the intended learning outcomes for the program | Some identified SLOs exist that reflect the intended learning outcomes for the program | Many, but not all, SLOs exist that reflect the intended learning outcomes for the program | A comprehensive list of desired SLOs exists which reflects all of the intended learning outcomes for the program |

| The delineated desired SLOs are relevant to the program’s goals | SLOs cannot be linked to the program’s goals | Some SLOs can be linked to the program’s goals | Many, but not all, SLOs can be linked to the program’s goals | All of the delineated desired SLOs are relevant to the program’s goals |

| Process/Delivery Outcomes (PDOs) | ||||

| A comprehensive list of desired individual PDOs exists | No identified PDOs exist | Some identified PDOs exist | Many, but not all, PDOs exist | A comprehensive list of desired individual PDOs exists |

| Each delineated desired PDO is linked to a specific corresponding SLO | No specific PDO can be linked to a specific corresponding SLO | Some specific PDOs can be linked to a specific corresponding SLO | Many, but not all, PDOs can be linked to a specific corresponding SLO | Each delineated desired PDO is linked to a specific corresponding SLO |

| Assessment Cycle | ||||

| An assessment cycle has been identified for each individual desired outcome | No assessment cycle has been identified for any outcome | An assessment cycle has been identified for a few outcomes | An assessment cycle has been identified for most, but not all, outcomes | An assessment cycle has been identified for each individual desired outcome |

| Methodology and Measures | ||||

| The assessment methods used captured data relevant to the desired outcomes | The assessment methods did not capture any data relevant to the desired outcomes | The assessment methods captured minimal data relevant to the desired outcomes | The assessment methods captured significant, but not complete, data relevant to the desired outcomes | The assessment methods used captured complete data relevant to the desired outcomes |

| The questions asked via the measurements are linked to specific desired outcomes | The questions asked via the measurements are not linked to specific desired outcomes | Some of the questions asked via the measurements are linked to specific desired outcomes | Many, but not all, of the questions asked via the measurements are linked to specific desired outcomes | All of the questions asked via the measurements are linked to specific desired outcomes |

| The assessment methods were utilized in a manner that captured all desired information on student learning (for assessment of SLOs) | The methods were utilized in a manner that did not capture information on student learning | The methods were utilized in a manner that captured some information on student learning | The methods were utilized in a manner that captured much, but not all, information on student learning | The assessment methods were utilized in a manner that captured all desired information on student learning (for assessment of SLOs) |

| Summative assessments were used | No summative assessments were used | N/A | N/A | Summative assessments were used |

| Formative assessments were used | No formative assessments were used | N/A | N/A | Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative) were used |

| Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative) were used (dichotomous) | Only one form of measurement was used | N/A | N/A | Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative) were used |

| Multiple measures were used to assess each desired outcome | Multiple measures were not used for each outcome | N/A | N/A | Multiple measures were used to assess each desired outcome |

| The student sample assessed was representative of the student population of interest | The student sample assessed was not representative of the student population of interest | N/A | N/A | The student sample assessed was representative of the student population of interest |

| The student sample assessed consisted of a large enough N to make informed decisions | The N of the student sample assessed was not large enough to allow for informed decisions | N/A | N/A | The N of the student sample assessed was large enough to allow for informed decisions |

| Outcome Data | ||||

| If desired outcomes were not achieved, the data informed why | If desired outcomes were not achieved, the data did not inform why any given outcome was not achieved | If desired outcomes were not achieved, the data informed why some of the desired outcomes were not achieved | If desired outcomes were not achieved, the data informed why many of the desired outcomes were not achieved | If desired outcomes were not achieved, the data informed why all of the desired outcomes were not achieved |

| The outcome data informs what needs to be done to improve student learning as the result of participation in the program (for assessment of SLOs) | The outcome data provides no information regarding what needs to be done to improve student learning as the result of participation in the program | The outcome data provides some information regarding what needs to be done to improve student learning as the result of participation in the program | The outcome data provides a good deal of information regarding what needs to be done to improve student learning as the result of participation in the program | The outcome data completely informs what needs to be done to improve student learning as the result of participation in the program |

| Follow-up | ||||

| Assessment processes allow feedback to students as learners (for assessment of SLOs) | The assessment processes did not allow feedback to students as learners | The assessment processes allowed partial feedback to students as learners | The assessment processes allowed much, but not extensive, feedback to students as learners | The assessment processes allowed extensive feedback to students as learners |

| Assessment is valued as part of the program’s culture | Assessment is not valued within the program’s culture | Assessment is valued as part of the program’s culture by few involved in the program | Assessment is valued as part of the program’s culture by most, but not all, involved in the program | Assessment is valued as part of the program’s culture by all involved in the program |

| The assessment process is sustainable | The assessment process cannot be sustained in its current form | Minimal aspects of the assessment process can be sustained in its current form | Much, but not all, of the assessment process can be sustained in its current form | The whole assessment process is sustainable in its current forum |

| Relevant stakeholders participated in the review of assessment processes | No relevant stakeholders participated in the review of the process for the assessment of the program | Some relevant stakeholders participated in the review of the process for the assessment of the program | Many, but not all, relevant stakeholders participated in the review of the process for the assessment of the program | All relevant stakeholders participated in the review of the process for the assessment of the program |

Table 3 proposes a sample model rubric to assess stakeholder learning resulting from participation in the assessment process, which I am calling the assessment of the assessment process. Please note that the term “appropriate stakeholders” in this rubric describes those specific stakeholders whose learning outcomes are under assessment. Here, again, the rubric is only an initial sample and would need to be changed depending on the goals of a particular program; not all stakeholders will need to achieve all or even the same desired learning outcomes.

Table 3

| Desired Participant Learning Outcome | Not Achieved | Minimally Achieved | Partially Achieved | Minimal Level Attained to Declare Outcome Is Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriate stakeholders involved know the definition of assessment in higher education | No stakeholders involved know the definition of assessment in higher education | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved know the definition of assessment in higher education | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved know the definition of assessment in higher education | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved know the definition of assessment in higher education |

| Appropriate stakeholders involved know the differences between evaluation and assessment | No stakeholders involved know the differences between evaluation and assessment | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved know the differences between evaluation and assessment | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved know the differences between evaluation and assessment | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved know the differences between evaluation and assessment |

| Appropriate stakeholders involved identify the general processes for engaging in assessment of the program | No stakeholders involved identify the general processes for engaging in assessment of the program | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved identify the general processes for engaging in assessment of the program | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved identify the general processes for engaging in assessment of the program | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved identify the general processes for engaging in assessment of the program |

| Appropriate stakeholders know what outcomes are being assessed during any given assessment cycle | No stakeholders involved know what outcomes are being assessed during any given assessment cycle | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved know what outcomes are being assessed during any given assessment cycle | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved know what outcomes are being assessed during any given assessment cycle | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved know what outcomes are being assessed during any given assessment cycle |

| Appropriate stakeholders understand the necessity of using multiple measurements for assessment of any individual desired outcome | No stakeholders involved understand the necessity of using multiple measurements for assessment of any individual desired outcome | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the necessity of using multiple measurements for assessment of any individual desired outcome | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the necessity of using multiple measurements for assessment of any individual desired outcome | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the necessity of using multiple measurements for assessment of any individual desired outcome |

| Appropriate stakeholders value the necessity of valid data to determine whether a desired outcome has been met | No stakeholders involved value the necessity of valid data to determine whether a desired outcome has been met | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved value the necessity of valid data to determine whether a desired outcome has been met | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved value the necessity of valid data to determine whether a desired outcome has been met | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved value the necessity of valid data to determine whether a desired outcome has been met |

| Appropriate stakeholders appreciate the role of technology in gathering outcome data | No stakeholders involved appreciate the role of technology in gathering outcome data | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved appreciate the role of technology in gathering outcome data | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved appreciate the role of technology in gathering outcome data | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved appreciate the role of technology in gathering outcome data |

| Appropriate stakeholders value the cyclical nature of assessment as dynamic | No stakeholders involved value the cyclical nature of assessment as dynamic | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved value the cyclical nature of assessment as dynamic | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved value the cyclical nature of assessment as dynamic | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved value the cyclical nature of assessment as dynamic |

| Appropriate stakeholders value the cyclical nature of assessment as on-going | No stakeholders involved value the cyclical nature of assessment as on-going | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved value the cyclical nature of assessment as on-going | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved value the cyclical nature of assessment as on-going | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved value the cyclical nature of assessment as on-going |

| Appropriate stakeholders understand the connection between the assessment process and programmatic decision-making | No stakeholders involved understand the connection between the assessment process and programmatic decision-making | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the connection between the assessment process and programmatic decision-making | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the connection between the assessment process and programmatic decision-making | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the connection between the assessment process and programmatic decision-making |

| Appropriate stakeholders understand the connection between the assessment process and institutional decision-making | No stakeholders involved understand the connection between the assessment process and institutional decision-making | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the connection between the assessment process and institutional decision-making | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the connection between the assessment process and institutional decision-making | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the connection between the assessment process and institutional decision-making |

| Appropriate stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can impact day-to-day experiences for students participating in the program | No stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can impact day-to-day experiences for students participating in the program | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can impact day-to-day experiences for students participating in the program | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can impact day-to-day experiences for students participating in the program | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can impact day-to-day experiences for students participating in the program |

| Appropriate stakeholders involved know how the outcome data will be used to improve student learning resulting from participation in the program | No stakeholders involved know how the outcome data will be used to improve student learning resulting from participating in the program | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved know how the outcome data will be used to improve student learning resulting from participating in the program | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved know how the outcome data will be used to improve student learning resulting from participating in the program | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved know how the outcome data will be used to improve student learning resulting from participating in the program |

| Appropriate stakeholders involved identify opportunities for integrating assessment into professional development for program providers | No stakeholders involved identify opportunities for integrating assessment into professional development for program providers | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved identify opportunities for integrating assessment into professional development for program providers | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved identify opportunities for integrating assessment into professional development for program providers | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved identify opportunities for integrating assessment into professional development for program providers |

| Appropriate stakeholders recognize how assessment can be used in the development of program providers’ evaluation structures | No stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can be used in the development of program providers’ evaluation structures | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can be used in the development of program providers’ evaluation structures | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can be used in the development of program providers’ evaluation structures | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can be used in the development of program providers’ evaluation structures |

| Appropriate stakeholders recognize how assessment can be used in developing program providers’ reward structures | No stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can be used in developing program providers’ reward structures | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can be used in developing program providers’ reward structures | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can be used in developing program providers’ reward structures | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved recognize how assessment can be used in developing program providers’ reward structures |

| Appropriate stakeholders identify strategies to acquire resources to act on assessment results | No stakeholders involved identify strategies to acquire resources to act on assessment results | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved identify strategies to acquire resources to act on assessment results | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved identify strategies to acquire resources to act on assessment results | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved identify strategies to acquire resources to act on assessment results |

| Appropriate stakeholders understand the significance of evaluating the previous cycle of assessment to prepare for the next cycle of assessment for any given desired outcome | No stakeholders involved understand the significance of evaluating the previous cycle of assessment to prepare for the next cycle of assessment for any given desired outcome | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the significance of evaluating the previous cycle of assessment to prepare for the next cycle of assessment for any given desired outcome | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the significance of evaluating the previous cycle of assessment to prepare for the next cycle of assessment for any given desired outcome | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved understand the significance of evaluating the previous cycle of assessment to prepare for the next cycle of assessment for any given desired outcome |

| Appropriate stakeholders have a positive perception of the assessment process | No stakeholders involved have a positive perception of the assessment process | Some of the appropriate stakeholders involved have a positive perception of the assessment process | Most, but not all, of the appropriate stakeholders involved have a positive perception of the assessment process | All of the appropriate stakeholders involved have a positive perception of the assessment process |

Although these rubrics are designed and identified here as post-assessment tools, they may also be used as checklists when planning and performing the initial assessment process. In this way, the assessment team can include appropriate methodological parameters and procedures before beginning the initial assessment cycle.

ASSESSMENT AND META-ASSESSMENT IN ACADEMIC ADVISING

The NACADA (2006, 2017b) “Concept of Academic Advising” emphasizes academic advising as a process involving teaching and learning. Advising supports institutions’ missions and goals through advising curricula, pedagogy, and SLOs (Robbins, 2016b; Robbins & Adams, 2013). Moreover, various scholars have outlined how and why academic advising should be understood as a form of teaching and learning (Crookston, 1972/2009; Ender et al., 1984; Hemwall & Trachte, 2003, 2005; Lowenstein, 2005; McGill, 2016; Miller & Alberts, 1994; Robbins, 2009, 2011). Keup and Kinzie (2007) and Kuh (2008) suggest that when effectively provided, academic advising serves as a significant predictor of student engagement with the college environment. Effective academic advising connects students with learning opportunities (Campbell, 2008; Rinck, 2006; Schulenberg & Lindhorst, 2008) as well as positively (albeit indirectly) influences student self-efficacy and the development of study skills (Young-Jones et al., 2013).

Much has been written regarding assessment of student learning in higher education over the last few decades (Angelo, 1995; Banta et al., 2016; Ewell & Cumming, 2017; Huba & Freed, 2000; Maki, 2002, 2004, 2010; Palomba & Banta, 1999; Suskie, 2001, 2009). More recently, this literature includes assessment of student learning resulting from academic advising (Campbell, 2008; Hurt, 2007; Powers et al., 2014; Robbins, 2009, 2011, 2016b; Robbins & Adams, 2013; Robbins & Zarges, 2011). Academic advising must be assessed in order to determine program effectiveness—that is, to determine whether students are achieving both educationally and developmentally as a result of advising (Maki, 2002, 2004; Robbins, 2009, 2011; Upcraft & Schuh, 1996). Thus, assessment is performed to ensure advising programs are accountable (Robbins, 2009, 2011, 2016b). In some cases, the mere existence of academic advising programs and processes require justification with assessment data. More positively, assessment data can provide support for programmatic modifications to improve the effectiveness of academic advising by guiding future planning and playing a role in budgetary requests and programmatic decisions (Robbins, 2016b).

Given the theoretical focus of academic advising as a form of teaching and learning and the importance of assessing advising, it is essential to determine the appropriateness and validity of academic advising assessment processes as a practical matter. This typifies the current conceptualization of evaluation of the assessment process as a component of meta-assessment. In addition, the NACADA (2017a) “Core Competencies”—concepts academic advisers are expected to understand to be effective advisers—suggest that academic advisers should not only engage in assessment of academic advising but also know the expected and desired outcomes for their respective programs. Assessment of adviser learning would capture whether or not advisers engaging in assessment have gained such knowledge, which serves as an example of assessing stakeholder learning resulting from the assessment process.

In 2014, the accreditation body, the Middle States Commission on Higher Learning, provided the following key questions for evaluating the assessment process: How engaged are institutional stakeholders in the process? How collaborative has the assessment process been? How well are the assessment results related to goals and objectives? Further, to what extent do the assessments have potential for revealing the true state of things no matter how uncomfortable? In addition, Suskie (2009) suggested that in order for any assessment to be effective, it must provide accurate information on what students have learned to inform decisions, have a clear purpose, engage all appropriate stakeholders, become a part of the campus culture, and focus on clear and important SLOs. These questions and expectations for assessment can inform the considerations included in the evaluation of the assessment process.

Additional questions included as part of the evaluation of the assessment of academic advising may be derived from the literature regarding assessment of academic advising. For example, Robbins (2009, 2011, 2016b) and Robbins and Zarges (2011) noted that all appropriate stakeholders must be included in the planning for assessment of academic advising. A corresponding evaluative consideration of the assessment process would be whether all appropriate stakeholders were indeed included. These same authors suggest that an assessment cycle be defined for each individual SLO being assessed; the evaluative consideration then becomes whether each SLO for academic advising has a distinct cycle. The requirement of multiple measures for the assessment of each academic advising SLO, which would be another consideration in the evaluation of the assessment process for academic advising, is also emphasized by these authors as well as the CAS (2019) Standards for Academic Advising Programs. Further considerations will depend on the vision, mission, and goals of the specific academic advising program in conjunction with the identified desired SLOs for the advising program.

CONCLUSION

Meta-assessment of any higher education program with desired SLOs is an important step toward ensuring the quality of the assessment process and the validity of outcome data. In this article, I have argued that meta-assessment needs to be included as part of the overall assessment of academic advising cycle. Moreover, in contrast to existing literature, I have proposed that assessment of stakeholder learning should be included as part of meta-assessment. I have also provided sample rubrics that may be adapted for use in the meta-assessment of advising or other educational programs. While the items included in the sample rubrics are based on a combination the assessment literature along with theoretical and practical considerations surrounding the assessment of advising, they remain suggested items and untested example rubrics. Thus, the sample rubrics provided should be amended and tested in future scholarship and in practice.

It must be acknowledged that adding the step of meta-assessment and/or assessment of stakeholder learning resulting from the assessment process may be a practical challenge. First, many programs—including academic advising programs—are not conducting true outcomes assessment of any kind. Performing assessment may be perceived as additional work for already busy practitioners, and adding meta-assessment will only intensify such a perception. Second, for programs already conducting outcomes assessment, adding meta-assessment, while methodologically appropriate, may likewise add to the work already involved in assessment endeavors. The literature on assessment of academic advising provides suggestions regarding gaining buy-in for assessment and making assessment activities part of day-to-day responsibilities and tasks to alleviate such concerns (Robbins, 2009, 2011, 2016b; Robbins et al., 2019; Robbins & Zarges, 2011).

In the future, meta-assessment should be added to all NACADA assessment development opportunities, including but not restricted to the NACADA Assessment Institute; the NACADA Summer Institute; NACADA expert consultations, which include assessment of academic advising; and the NACADA Clearinghouse documents. In addition, academic advising programs conducting meta-assessment and using rubrics such as those proposed here need to provide data on the use of the rubrics. Such data will be helpful locally for any given academic advising program, while the collection of such data across academic advising programs nationally and globally would benefit the field of academic advising as a whole. The latter effort may be an initiative for the NACADA Assessment Committee or for the NACADA Center for Research at Kansas State University in regard to the Center’s goal of “advancing the scholarly practice and applied research related to academic advising” (NACADA, 2018).